Will’s Race for Home Discussion Questions

Download the Discussion Questions here.

Download the Discussion Questions here.

Download the Will’s Race for Home Educator’s Guide for your classroom! You will find Before, During, and After Reading activities to perform in the classroom.

Download the Paradise on Fire Book Club Guide for your classroom!

This guide was created by Little Brown and Company

www.littlebrownlibrary.com

Jewell Parker Rhodes’ novel Ghost Boys has been picked up to be filmed as a major motion picture.

Byron Allen’s Entertainment Studios Motion Pictures has acquired global rights to Ghost Boys, Jewell Parker Rhodes’ 2018 novel for young readers that weaves genres to explore what happens after a Black child is killed by a white police officer.

Said Rhodes, whose other middle-grade novels include the bestsellers Magic City, Paradise on Fire and Towers Falling: “I’m delighted Byron Allen’s movie division will create an inspiring feature film to empower us to be more empathetic and to ‘bear witness’ against social injustice. Protecting all children’s innocence and humanity is paramount. I’m not surprised that it was an amazing youth, Mr. Allen’s daughter, who helped advocate for Ghost Boys to become a movie. I’m thrilled and humbled to have Ghost Boys adapted and transformed to a new life.”

Via Open Up Resources:

“Discover Ghost Boys (Grades 5-7) by Jewell Parker Rhodes with your students and have meaningful conversations on what’s happening around the U.S.

So many of us are searching for solutions to engage our students and children in conversations about what is happening in our country. How do we support young people to think critically about the social justice issues that affect their lives and communities, and make meaning of the legacy of systemic racism that we’re grappling with as a nation?

We’re sharing our first FREE Reading with Relevance guide—a practical, easy-to-use resource for engaging the young people in your classroom, and your life, in empathy-building conversations about racism and injustice in America today.”

Download the Ghost Boys Educator’s Guide for your classroom! You will find curriculum resources for lessons on Civil Rights/BLM history, prejudice, and leading complex classroom dialogues for ages 8-12 and up.

This guide was developed by educator and bookseller Rebekah Shoaf of Boogie Down Books, with research by Steve Jozef and contributions by teachers Rachel Bello, Eric Burnside, Maziel Concepción, Alicia Lerman, Liz Madans, Sheilah Papa, Audrey Salazar, and Rebecca Seering.

Little Brown and Company

www.littlebrownlibrary.com

Download the Sugar Educator’s Guide for your classroom! You will find curriculum resources for lessons on African American heritage, history, the post-abolitionist era, and immigration for ages 8-12 and up.

This guide was prepared by Jennifer McMahon.

Little Brown and Company

www.littlebrownlibrary.com

China’s Yangtze River (sometimes called Changjiang, “the long river”) is the 3rd longest in the world at 3,988 miles. The Yangtze is home to many endangered species, like the Chinese Alligator and Yangtze sturgeon, as well as the extinct river dolphin. It begins near the border of Tibet and ends in the East China Sea, spanning almost the entire width of the country.

The Yangtze is like America’s Mississippi River (the 4th longest in the world at 2,530 miles) in many ways. Both of these long and winding rivers divide each country in half, marking important cultural differences from one side to the next. Both end in large delta systems that are centers for trade. Some of the most important cities in both China and America developed on the shores of these rivers. People have tried to control these rivers with damns and huge levee systems in order to prevent flooding and harness the power of the river for human use. Both rivers have been sites of international interest, with people from many countries around the world seeking to use and control the river for their own gain.

The Chinese Zodiac is an astrological system that relates each calendar year to an animal. There are twelve animal signs altogether, one for each year of the zodiac. The animal signs repeat every 12 years, which is the length of the zodiac cycle. The first sign of the cycle is the rat, who is fast and sneaky, and the last is the pig, who is slow but smart. Each animal is associated with different traits, which a person born in that year is also thought to possess. Someone born in the year of the dog would seem honest, loyal and friendly, while a person born in the year of the dragon would be strong, proud and fiery. Each sign is also enhanced by the qualities of an element, either earth, water, metal, wood, or fire.

The Chinese name for the Sichuan Opera, Bian Lian, literally means “Face-Changing” because of the elaborate use of masks. Performers wear brightly colored costumes and move to quick, dramatic music. They wear vividly colored masks, which they change within a fraction of a second. Only the sons of performers are allowed to learn the secrets of the Sichuan Opera; no women, and no outsiders, are permitted to perform this masked dance.

In China, Buddhism is the most popular religion. It is based on the teachings of the Supreme Buddha, which means “the enlightened one.” Like Christianity, Buddhism is based on an actual man, named Siddhārtha Gautama, who lived in India around 480 BCE. Buddha taught his people that through meditation and moderate living one can achieve Nirvana, or perfect peace of mind. Today the Buddha is depicted in paintings and statues all over the world. He is usually seated cross legged while he meditates, wearing robes over his round belly, a happy expression on his face.

In China, it was customary for men to wear their hair in Queues, or brained ponytails, until the early 20th century. The hairstyle consisted of the hair on the front of the head being shaved off above the temples every ten days and the rest of the hair braided into a long ponytail, which would grow long enough to reach the man’s waist. For hundreds of years every man in China was forced to wear this hairstyle; if a man refused to wear his hair in a queue, he would be executed for treason. For this reason, it became very important to Chinese men to keep their queues, even after they immigrated to America, because it was a part of their identities. Many Americans did not like or understand the queues, and sometimes even tried to force Chinese men to shave them off.

Br’er Rabbit is a central figure in the Uncle Remus stories of the Southern United States. He is a trickster character who succeeds by his wits rather than by brawn. The story of Br’er Rabbit, a contraction of “Brother Rabbit”, has been linked to trickster figures in both African and Cherokee cultures. Many people believe that in the American stories Br’er Rabbit represents the enslaved African who uses his wits to overcome circumstances and to exact revenge on his adversaries, representing the white slave-owners. Though not always successful, his efforts made him a folk hero. Disney later adapted the character for their movie Song of the South, and today Disneyland’s ride “Splash Mountain” is based on his stories.

Download the Towers Falling Educator’s Guide for your classroom! You will find curriculum resources for lessons on history, social studies, and prejudice for ages 8-12 and up.

This guide was prepared by Erica Rand Silverman and Sharon Kennedy, former English teachers and co-founders of Room 228 (www.rm228.com), along with Kelly Hoover, a Colorado elementary school teacher. Erica and Sharon were teaching in NYC on September 11 and feel honored to have worked on this guide.

Little Brown and Company

www.littlebrownlibrary.com

I press the power button and the screen lights up, and there he is, the sweaty weather man.

Mama Ya-Ya sits up further. I sit beside her, a pillow behind my back. At the bottom of the bed, Spot is lying on his back, his belly up. If we were watching Oprah, we’d be having a good time.

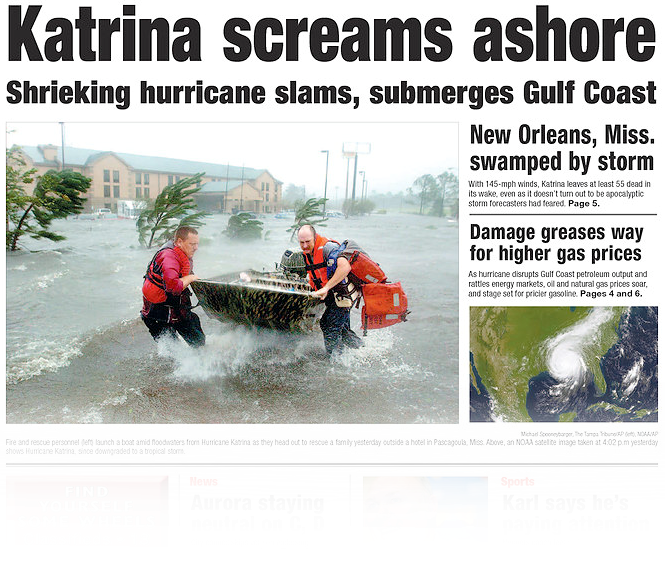

The weatherman says, “Katrina is headed directly for New Orleans. If you haven’t gotten out, buckle down. It’s going to be a wild ride. Perhaps devastating.”

I go to Mama Ya-Ya’s window. Peek between slats. The sun’s gone.. The moon is yellow. The wind is whistling.

“It’s coming,” I hear Mama Ya-Ya say,

I shiver. Tell myself not to be afraid. We’ll survive the hurricane.

Ghosts told me so.

I must’ve fallen asleep, because when I wake, Mama Ya-Ya has her hands thrown over her head and she is sleeping deeply. The lamp on the nightstand makes the room glow, seem unreal. Nothing’s moving. No mice—they skitter at night. Not even fat water bugs that come out when you turn down the lights.

Nothing. Silence, inside and out.

I swear I can’t hear a thing. No one’s having a party. No fighting, laughing, singing. No words drifting up from the porches. Nothing.

The quiet makes me think I’m going to die. Like Mother Nature has sucked up everything—all sounds, winds, human talk and cries. A VACUUM. ABSENCE OF MATTER.

I worry I’ll be sucked up, too.

But the silence doesn’t last.

Read the rest of Ninth Ward

Amazon

IndieBound

Barnes & Noble

Powell's Books

Download the Ninth Ward Educator’s Guide for your classroom! You will find curriculum resources for reading & discussion, writing & vocabulary, math, science and history for ages 8–12.

Educator’s Guide prepared by Tracie Vaughn Zimmer, a reading specialist and children’s author.

Little Brown and Company

www.littlebrownlibrary.com

Download the Bayou Magic Educator’s Guide for your classroom! You will find curriculum resources for fairy tales & folklore, environment, and family for ages 8–12 and up.

Educator’s Guide prepared by Betty Carter, an independent consultant and professor emerita of children’s and young adult literature at Texas Woman’s University.

Little Brown and Company

www.lbschoolandlibrary.com

Hurricane Katrina Before and After

Here is an interesting look of New Orleans during the hurricane vs. how it looks now through pictures. Via MSNBC.

Rising from Ruin

A special report by MSNBC that chronicles the rebuilding process of two Gulf Coast towns devastated by Hurricane Katrina, including profiles of town residents and their stories. Via MSNBC.

When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts

This is a film by Spike Lee Information on a documentary about the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. This film won the Orizzonti Documentary Prize and one of two FIPRESCI awards. It won three Emmy awards. Via Wikipedia.

The Ninth Ward or 9th Ward is a distinctive region of New Orleans, Louisiana that is located in the easternmost downriver portion of the city. It is geographically the largest of the 17 Wards of New Orleans. The 9th Ward neighborhood was thrust into the nation’s spotlight during Hurricane Katrina. Much of the 9th Ward on both sides of the Industrial Canal experienced catastrophic flooding in Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The majority of the damage was caused by storm surge. There were multiple severe levee breaks along both the MRGO and the Industrial Canal.

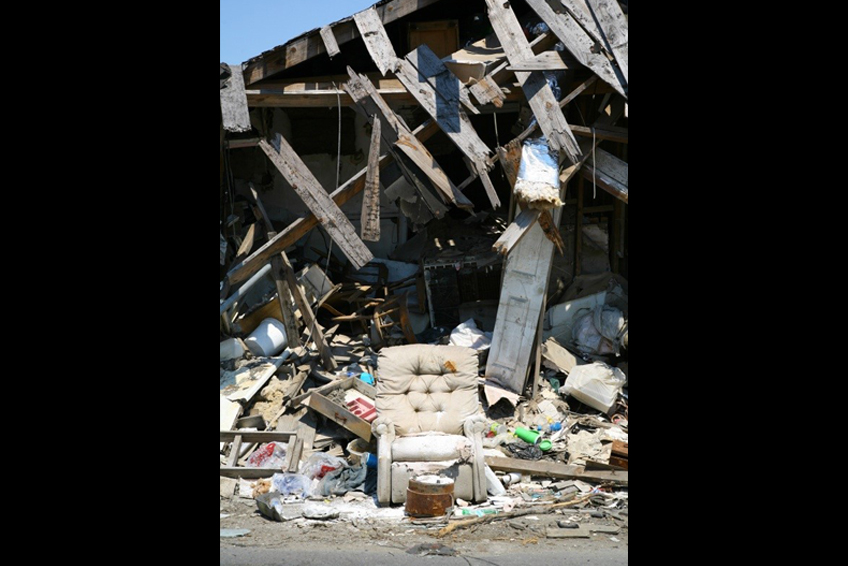

A house sits on top of a car in Ward 9, New Orleans, 21 days after the hurricane.

Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans over a year after Katrina, showing the remaining devastation.

A chair sits in front of what was a home in the Lower Ninth Ward neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana. This is about 1/4 mile of where the levy broke. Essentially a river of water hit this house destroying it. This photo was taken about 9 months after the storm.

By Jewell Parker Rhodes

I wrote my first children’s book, The Last Scream, when I was eight years old. It was a very thin book, bound in yellow construction paper, and illustrated by me! I read it aloud to my Homewood Elementary School classmates and thought I was in heaven.

I was the kid who preferred books to dolls. I was the kid they called “little professor” and the one always asking, teachers and librarians, “More, please.” Books were better than food.

It’s taken me forty years to be ready to write Ninth Ward, my second children’s book. Why so long? I was waiting for the magical moment when I felt the right story call to me.

In 2005, when Hurricane Katrina hit, I was transfixed by new stories and images of the survivors. I always kept asking myself, “What about the children?”

My own family had experienced the 1994 Northridge Earthquake; my children were five and three. My three year old stopped speaking; my five year old, kept hiding. For a week, my husband, children, and two dogs all lived on our “big bed” in a broken house without utilities. But we were all safe, and we were all together—I couldn’t imagine the trauma of dislocation and death Katrina caused to Louisiana families.

Still, it wasn’t until 2008 when Hurricane Ike was threatening New Orleans, that Lanesha’s voice spoke to me:

“They say I was born with a caul, a skin netting covering my face like a glove. My mother died birthing me. I would’ve died, too, if Mama Ya Ya hadn’t sliced the bloody membrane from my face.”

There she was! An orphan, someone nurtured with care by an elder, and someone born with a caul, a sign of “second sight.” I just knew Lanesha was a survivor—a strong, resilient, and heroic child to be celebrated. With loving from Mama Ya Ya, friends, and the companionship of a dog, Lanesha would endure. Lanesha is the child who throws her arms about herself and says, “I like me.”

With that voice, I knew I had my next story.

I was the child with far less self-esteem who sometimes hid in the closet, crying. My mother abandoned me as an infant and Grandmother Ernestine raised me. Grandmother, like Mama Ya Ya, was a conjure woman, believing in ancestors and holistic healing. She was the community griot, telling stories to heal us all. I was less cool, less smart, and less creative than Lanesha. Lanesha is the character I would’ve loved reading about!

Ninth Ward has sad moments but it isn’t a sad story. Just as the levees break, life sometimes seems unbearable. But Lanesha shares her story to inspire others—I think it’s a story of triumph—a particularly New Orleans triumph.

I was born in Pittsburgh but my very first adult novel was set in New Orleans and honored its mixed-blood stew of social and spiritual traditions. I’ve been writing about, visiting New Orleans ever since. I think I might have lived there in another life.

My entire life has been a journey on the way to writing Ninth Ward. Grandmother, my community, and teachers and librarians showered me with guidance and love. They all gave birth to Lanesha. A girl with hope, a big heart, and a firm belief that always, eventually, “The universe shines down with love.”

A caul

12

Died giving birth to her

17

Romeo and Juliet

Her mother’s ghost

Different shades of blue

Life

In a drive-by shooting

Midwife

Math

TaShon

An engineer

Uptown

The grocery store

Vietnam

Florida

A teacher’s edition math book (pre-algebra) to practice problems

The Superdome

Bridges

That she wanted to have Lanesha very much and/or that she came to his church

They are foods that will last a long time before they spoil, in case they lose electricity.

They don’t have enough money/any way to leave

In the tub

A Sunday

A woman (looking for someone named Lyle) gives him a ride

She knows the flood is coming

The Mississippi River

A tree trunk (or math)

A tree trunk (or math)

82-12= 70 years

You’ve written other books that take place in New Orleans and write with such affection for the characters if the Ninth Ward. Your connection to the South seems to run deep. Can you talk a little about that connection?

My Grandmother Ernestine who raised me was a southern girl. She’d migrated North seeking a better life for her children; but I always sensed that our urban ghetto didn’t compare to the beauty of the South. Grandmother, never finished elementary school, but she was a terrific storyteller and a gifted healer. She practiced her “rootwork” on us, kids, by insisting on our daily dose of cod liver oil and using herbs for healing burns, cuts, and colds. Grandmother, like Mama Ya-Ya, also believed in signs. For her, numbers, colors, dreams, all had meaning. She’d also told us that we had to burn the leftover hair in our brush, because if we didn’t and a bird found a strand and used it for its’ nest, our hair would “fall right out.” Grandmother was also the wife of an AME Methodist minister and, as in New Orleans, blended African-based spirituality with Christianity.

So, short answer: I’m not a southern girl but I was raised by one. My upbringing provided the perfect entry to understanding the complicated, magical, and mystical world of New Orleans!

Within the first few paragraphs of Ninth Ward readers know that the relationship Mama Ya-Ya and Lanesha have is special. The details the girl shares about Mama Ya-Ya tell us so much about the woman, the child, and their life together—and your dialogue is pitch-perfect. Do your characters speak to you first, or do you visualize them, then give them voice?

I need to hear my character’s voice before I can write about them.

In 2005, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, I was transfixed by new stories and images of the survivors. I kept asking, “What about the children? Still, it wasn’t until 2008 when Hurricane Ike was threatening New Orleans that Lanesha spoke to me. I wrote furiously, trying to honor Lanesha’s voice. As I wrote, Lanesha became more real—became a lively, wonderful three-dimensional girl.

Mama Ya-Ya’s voice is based upon my memory of my grandmother’s voice. However, Mama Ya-Ya’s vulnerability surprised me. She becomes quieter and quieter as the storm approaches. I think children are shocked when grown-ups are confused and don’t know what to do. I was shocked by Mama Ya-Ya’s silence. Eventually, I realized her silence became a “sound”—a cue for Lanesha to grow up.

While Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Ninth Ward form the backdrop of your book, you tell that story through individuals—Mama Ya-Ya, Lanesha, and TaShon (and his dog, Spot)—all of whom possess unique abilities or characteristics, and all described as abandoned, lost, or as orphans at some point. Tell us a little about them.

Everyone knows the story of Hurricane Katrina but we don’t know the particulars. I wanted readers to see themselves in my characters and to connect with their humanity.

All children should have a loving elder, like Mama Ya-Ya. And every child, like Lanesha and TaShon, should develop a bond with someone they didn’t see, at first, as a potential best friend. Add experiencing a pet’s love and perspective, and, I think, you have the recipe for a very good life.

Still, my characters are all damaged in some way. Spot has been abandoned and abused; TaShon is the alienated, short kid, not quite nurtured enough by his hard-working parents; Mama Ya-Ya has lost her fiancé and her community’s faith in her midwifery; and Lanesha has been orphaned. When I was writing the story, I didn’t think of these “damaged” connections and interconnections, they just happened. I think I must’ve been echoing the losses in my own life. My mother had abandoned me as an infant and I often felt isolated and rejected. I didn’t have a pet though I wanted one. And my grandmother wasn’t perfect but often frazzled and harried caring for five grandchildren and cooking and cleaning for a large extended family. And yet—my childhood was good.

So—what does this mean? I’m not entirely sure. Maybe all along I’ve been trying to say that perfect families and perfect lives don’t exist. Nonetheless, we can create, if need be, alternative families. We can have friendships without betraying our sense of self. We can care and love an animal that in turn cares and loves us.

To me, Ninth Ward is a joyful book. Lanesha is the child strengthened by love and friendship.

Early in the book, before the storm is arrives, Lanesha remarks about her day, “I thought this day was going to be ordinary. But it was full of surprises.” To me those lines say so much about her incredible strength and her positive outlook. Where does this strength come from?

Lanesha’s strength comes from Mama Ya-Ya’s unconditional and abiding love. She lives in a neighborhood that despite poverty, provides her with a sense of family.

Lanesha also has wonderful teachers who challenge her mind. When rational thought is needed, she is capable of solving real-life problems using her math skills. She also has vocabulary words such as “fortitude” that help her contextualize her experience. Education gives Lanesha a measure of control over her life. She also loves to read to find out things (from her home Encyclopedia Brittannica) and to feel emotions garnered from stories like Romeo & Juliet (using film and books from the public library). Lanesha also draws strength and optimism from her creative life. Her colored pens allow her to reaffirm her self-love. “I [heart] Me.” Her puzzle pieces allow her to see beauty and imagine new landscapes such as Paris. Lanesha draws strength, too, from being able to paint her bedroom blue. She’s learned that she can complete projects on her own.

Faith also supports Lanesha’s positive outlook. Her perception of the world isn’t static. There are things seen and unseen. Good and bad can ebb and flow. She is not afraid of ghosts, of death. In her world, the human spirit doesn’t die. Most significantly, she’s been taught, always, eventually, “the universe shines down with love.”

Lanesha was born with a caul—what’s the significance of her caul? Several characters in the book see ghosts and ghosts—both neutral and benevolent—are a real presence in the book. Can you talk about them. What is it they are looking for?

Lanesha, when she first spoke, told me she was “born with a caul.” A caul is a portion of the amniotic sac that sometimes forms a veil over a newborn’s face. In folklore, this means the child will have “sight.” By announcing her gift, Lanesha was heralding her southern heritage. She was telling me, matter-of-factly, that she accepted and experienced mysteries.

It’s impossible to live in New Orleans without experiencing remnants of the past. The architecture, the churches, the above ground cemeteries, and even the music, all incorporate ghosts and echoes of slavery and French and Spanish colonization. Particularly, for African Americans, New Orleans is where African-based spiritual beliefs blended with Catholicism. It is the birthplace of ragtime and jazz, rhythms inspired by African drums. It is a place where medicinal healing by slaves and native peoples produced a “roots” based, holistic tradition. In New Orleans, many African Americans do not believe the dead are accessible. It is not uncommon for someone to talk about receiving comfort and guidance from their ancestors. Dreams, spiritual visitations, and talking with the dead are all part of folklore and cultural and religious traditions.

The ghosts in the book help, I think, to deepen the “sense of place.” New Orleans is a uniquely American city—a mixed-blood stew, historically, and in the present.

Most of the ghosts

aren’t ready to move on. They feel comfortable, like Lanesha, living in two worlds, the seen and the unseen. In a sense, the ghosts are Lanesha’s alternative community.

In “coming of age,” tales, there is always a moment where the child ascends. Mama Ya-Ya is old with waning powers. Her inability to interpret Katrina’s signs is a call for the next generation, for Lanesha, to take charge. This is a natural cycle. The young with their energy and education replace elders who sustained the world as they knew it. Lanesha is getting ready to shape the world, as she knows it—and she “knows” the world as Mama Ya-Ya and her teachers have taught her. The ghosts keep silent about the impending storm because 1) they’ve seen it all, their sense of time is infinite; but their silence, coupled with Mama Ya-Ya’s silence, provides space for Lanesha to find her voice. And she does. To me, this is life. Parents, teachers, and ancestral ghosts (history, if you prefer) will ultimately give way to the next generation. Children will, one day, rule the world.

Mention of bridges appear throughout the book. Lanesha’s teacher tells the girl she would make a great bridge builder/engineer. Mama Ya-Ya says that Lanesha’s “feet bridge two worlds.” What can we hope for a bright future for Lanesha? (For New Orleans?)

Bridges kept many New Orleans citizens above water. Bridges took then to a safer place. Bridges occupy a nether world, a space that seems to defy air, land, and water. Bridges are signifiers for human ingenuity, intelligence, and interconnected-ness.

I have always thought New Orleans would thrive, no matter what. Hurricanes, land erosion, the BP oil spill have challenged my optimism. But there are thousands of Laneshas and TaShons in New Orleans who will not be daunted. As nature heals what humanity has done to it, I think lots of good people will be there, too—healing and loving a unique state back to health. It will take time. Louisianans have the requisite grit, determination, and abounding love.

This is your first for young readers. How did that happen? (& have you thought about writing others for this audience?)

I have ALWAYS wanted to write for children. My entire life I’ve been trying to become good enough, confident enough to write for children. Now that Ninth Ward is born, I feel reenergized. I’ve drafted a young adult novel and I’m starting on a new middle grade adventure.

Everybody likes sugar.

Folks say, “There wouldn’t be any good food without sugar.” Like rhubarb cobbler. Blueberry pie. Yellow cake.

But I hate sugar. I won’t eat it. Not ever.

“No sweets, just savories,” I used to tell Ma. “Corn bread. Grits.” Even nasty okra and green beans are better than sugar.

There’s all kinds of sugar. Crystals that turn lemons into lemonade. Syrup that cools into taffy. Or pralines, brittle. There’s even sugarcane you can suck until your lips wrinkle and pucker.

In the mill, there’re mountains of sugar ready to be shipped from Louisiana to the whole wide world.

Ma would say , “Most folks think sugar is something in a tin cup or a china bowl. They don’t know sugar is hard.”

“Hard,” I’d echo as she poured well water into a bowl.

“Months of planting, hoeing, harvesting. Bones aching , sweat stinging your eyes. Dirt clings everywhere.”

“Beneath nails, toes. Even in my hair,” I’d complain before splashing my face with water.

Me and Ma always smelled of sugar, sweat, and dirt.

“What did I smell like when I was born?”

“Spring,” she’d whisper, wiping my face dry. “Not Planting-Day spring. Just spring. Blooming, lemony, and fresh.”

I wish I could remember that clean smell.

When I was two days old, Ma strapped me to her back and cut cane.

Nights, we ate cornmeal cakes. Then me and Ma would lie on our hay mattress on the packed-dirt floor.

“Sugar’s hard,” she’d sigh, kissing my cheek, twice, before sleep.

Before another day tending cane.

River Road is almost nothing but cane. There’re two rows of slave shacks. Mostly empty now. There’s the big plantation house where the Willses live. The mill where cane is boiled and dried into crystals. The stable and henhouse.

The rest is cane . Growing ten feet high, row after row, as far as the eye can see. When wind blows, cane hisses, comes alive, swaying like a dancing forest. Thin, pointy leaves lick the air, flapping like streamers. It’s pretty. ’Til you get close. Then sugar gets nastier than any gator.

Sugar bites a hundred times , breaking skin and making you bleed. Each leaf has baby teeth on all its edges. Even with work gloves, tiny red pricks itch everywhere. My cheeks get smacked. By harvest’s end, my face, hands, and arms are all cut up.

Outside River Road Plantation, nobody cares who cuts cane. Nobody cares my hand swings the machete, bundles, drags stalks onto the cart.

At River Road, my hands are the youngest. Everyone else’s hands, except Lizzie’s (she’s two years older than me), are old and wrinkled. Grown hands, stiff and scarred. Sometimes the old folks put their hands in warm water with peppermint to heal. Or rub them with fatback sprinkled with cayenne.

I’ve lived at River Road my entire life. Cane is all I know. Cutting, cracking, carrying pieces of cane. My back hurts. Feet hurt. Hands get syrupy. Bugs come. Sugar calls— all kinds of bugs, crawling, inching, flying. Nasty, icky bugs.

I hate, hate, hate sugar.

During harvest, Mister Wills sets lamps so folks can cut cane all night. “Cane won’t wait,” he says. He shouts, “Cane time, cuttin’ time.” Or he snarls, “Two bits extra for the most cane cut.” Then, everybody speeds up and there’re more tiny bites. Just like teeth chew rows of corn, sugar-teeth chew on you.

Mister Wills keeps complaining, “Not enough cane workers.”

I think, Why isn’t he helping, then?

Mister Wills just walks and watches everyone work. Behind him, Tom, the Overseer, cracks the whip, spraying dirt.

Since Emancipation, there’re not enough workers. Almost everyone young enough, without gnarled, crinkly brown hands, has gone north.

“Some folks are scared to leave,” said Ma. “They say, ‘The bad I know is better than the bad I don’t.’ They don’t believe they have strength left for adventure.”

“We’re ready for adventure. We’re strong.”

“That’s right,” said Ma, hugging me close.

We waited for Pa, who was sold right after I was born, to come back for us. We were going to run away. Head north. We waited and waited. When the war started, Ma whispered, “Pa’s fighting for the Union. I just know it. Helping to free us.” We waited for him, proud, hoping. The war ended. President Lincoln won. Still, we waited. Five years of freedom and Pa still didn’t come.

Then Ma got sick and died. Her strength drained like water.

I’m ten now. ’m not a slave anymore.

I’m free.

Except from sugar.

Read the rest of Sugar

Amazon

IndieBound

Barnes & Noble

Powell’s Books

No

The hyena

Mr. and Mrs. Beale

Both Billy and Sugar are captain!

Br’er Rabbit

Lizzie

Billy

Africa

15 tree

1871

“Ni hao” (pronounced “Knee-how”)

They are afraid the Chinese workers will take their jobs.

His name “Bo”

Year of the Monkey

Emperor Jade

Rice balls

“Survive.”

Her whistle

He tricks Hyena into jumping on one of the buckets on the pulley, bringing Hyena down into the well and Rabbit up out of the well.

Yes

Red

Gators

Yellow

Theox

To rescue Jade

Tom, the overseer

Mr. Beale

He says he has sold the mill.

They bow to each other

North to St. Louis

Madison Isabelle Lavalier Johnson

Dionne, Aleta, Layla and Aisha

“Did my firefly come?”

A chicken

Louisiana bayou called Bon Temps

A hero

Bear

Yes

Old Jake

Yes

Mami Wata

Lavalier Plantation

Sorrow

She sees the oil spill, and feels herself drowning in it

Grandmere says she hoped Maddy would see her, and that the mermaid is Mami Wata

Yes

Mami Wata blows bubbles into Maddy’s lips

Yes

Oil tunnels

“Yes” and French

She kicks him and calls him

Stew

Sassafras

Crude

Gulf of Mexico

A pelican

Maddy asks Mami Wata to call on other mermaids to help them

Yes

To promise that Maddy will be able to spend every summer with Grandmere, Bear and her friends in Bon Temps

Listed below are some fun and educational links having to do with Sugar. Explore the Laura Plantation as it is today. Visit the sites about Br’er Rabbit’s stories. Learn more about Chinese immigrants like Beau and Master Liu.

Laura Plantation is the inspiration for River Road Plantation.

This link gives info about the Br’er Rabbit tales as America folklore.

This link is an excellent resource re: Chinese exclusion—the time period when my Sugar’s Chinese friends had no pathway to US citizenship

A graphic novel: Escape to Gold Mountain: A Graphic History of the Chinese in North America

Recent Comments