You’ve written other books that take place in New Orleans and write with such affection for the characters if the Ninth Ward. Your connection to the South seems to run deep. Can you talk a little about that connection?

My Grandmother Ernestine who raised me was a southern girl. She’d migrated North seeking a better life for her children; but I always sensed that our urban ghetto didn’t compare to the beauty of the South. Grandmother, never finished elementary school, but she was a terrific storyteller and a gifted healer. She practiced her “rootwork” on us, kids, by insisting on our daily dose of cod liver oil and using herbs for healing burns, cuts, and colds. Grandmother, like Mama Ya-Ya, also believed in signs. For her, numbers, colors, dreams, all had meaning. She’d also told us that we had to burn the leftover hair in our brush, because if we didn’t and a bird found a strand and used it for its’ nest, our hair would “fall right out.” Grandmother was also the wife of an AME Methodist minister and, as in New Orleans, blended African-based spirituality with Christianity.

So, short answer: I’m not a southern girl but I was raised by one. My upbringing provided the perfect entry to understanding the complicated, magical, and mystical world of New Orleans!

Within the first few paragraphs of Ninth Ward readers know that the relationship Mama Ya-Ya and Lanesha have is special. The details the girl shares about Mama Ya-Ya tell us so much about the woman, the child, and their life together—and your dialogue is pitch-perfect. Do your characters speak to you first, or do you visualize them, then give them voice?

I need to hear my character’s voice before I can write about them.

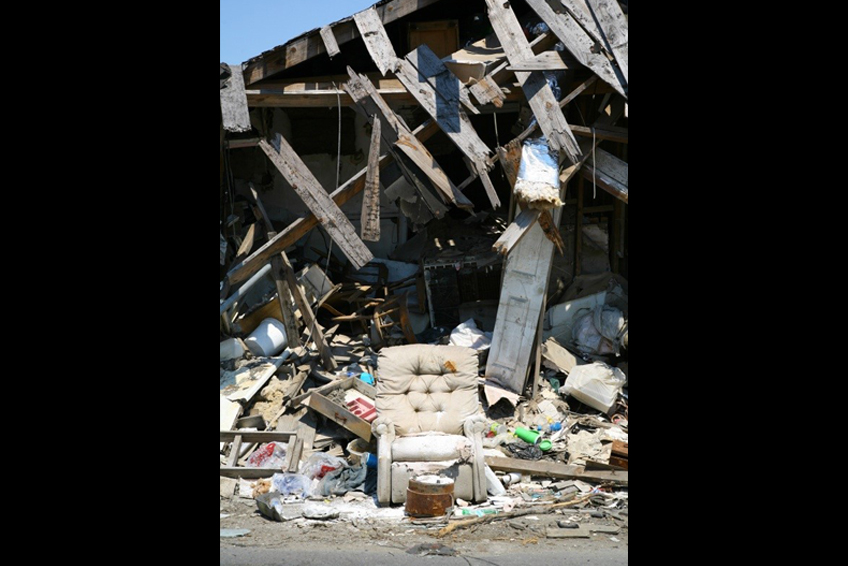

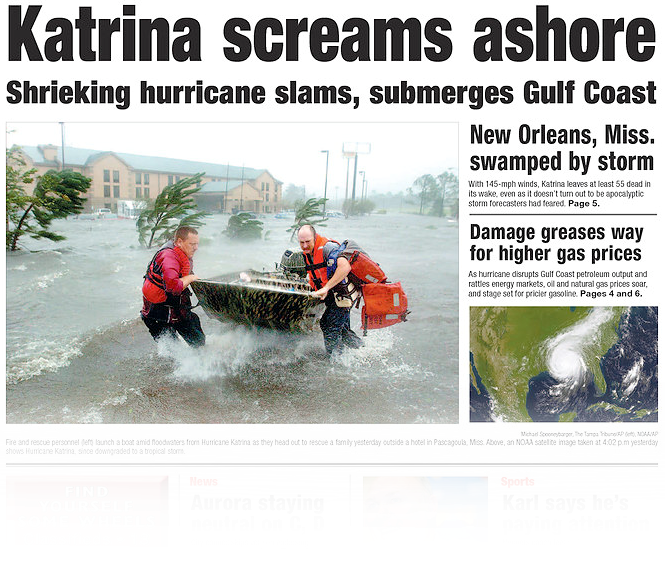

In 2005, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, I was transfixed by new stories and images of the survivors. I kept asking, “What about the children? Still, it wasn’t until 2008 when Hurricane Ike was threatening New Orleans that Lanesha spoke to me. I wrote furiously, trying to honor Lanesha’s voice. As I wrote, Lanesha became more real—became a lively, wonderful three-dimensional girl.

Mama Ya-Ya’s voice is based upon my memory of my grandmother’s voice. However, Mama Ya-Ya’s vulnerability surprised me. She becomes quieter and quieter as the storm approaches. I think children are shocked when grown-ups are confused and don’t know what to do. I was shocked by Mama Ya-Ya’s silence. Eventually, I realized her silence became a “sound”—a cue for Lanesha to grow up.

While Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Ninth Ward form the backdrop of your book, you tell that story through individuals—Mama Ya-Ya, Lanesha, and TaShon (and his dog, Spot)—all of whom possess unique abilities or characteristics, and all described as abandoned, lost, or as orphans at some point. Tell us a little about them.

Everyone knows the story of Hurricane Katrina but we don’t know the particulars. I wanted readers to see themselves in my characters and to connect with their humanity.

All children should have a loving elder, like Mama Ya-Ya. And every child, like Lanesha and TaShon, should develop a bond with someone they didn’t see, at first, as a potential best friend. Add experiencing a pet’s love and perspective, and, I think, you have the recipe for a very good life.

Still, my characters are all damaged in some way. Spot has been abandoned and abused; TaShon is the alienated, short kid, not quite nurtured enough by his hard-working parents; Mama Ya-Ya has lost her fiancé and her community’s faith in her midwifery; and Lanesha has been orphaned. When I was writing the story, I didn’t think of these “damaged” connections and interconnections, they just happened. I think I must’ve been echoing the losses in my own life. My mother had abandoned me as an infant and I often felt isolated and rejected. I didn’t have a pet though I wanted one. And my grandmother wasn’t perfect but often frazzled and harried caring for five grandchildren and cooking and cleaning for a large extended family. And yet—my childhood was good.

So—what does this mean? I’m not entirely sure. Maybe all along I’ve been trying to say that perfect families and perfect lives don’t exist. Nonetheless, we can create, if need be, alternative families. We can have friendships without betraying our sense of self. We can care and love an animal that in turn cares and loves us.

To me, Ninth Ward is a joyful book. Lanesha is the child strengthened by love and friendship.

Early in the book, before the storm is arrives, Lanesha remarks about her day, “I thought this day was going to be ordinary. But it was full of surprises.” To me those lines say so much about her incredible strength and her positive outlook. Where does this strength come from?

Lanesha’s strength comes from Mama Ya-Ya’s unconditional and abiding love. She lives in a neighborhood that despite poverty, provides her with a sense of family.

Lanesha also has wonderful teachers who challenge her mind. When rational thought is needed, she is capable of solving real-life problems using her math skills. She also has vocabulary words such as “fortitude” that help her contextualize her experience. Education gives Lanesha a measure of control over her life. She also loves to read to find out things (from her home Encyclopedia Brittannica) and to feel emotions garnered from stories like Romeo & Juliet (using film and books from the public library). Lanesha also draws strength and optimism from her creative life. Her colored pens allow her to reaffirm her self-love. “I [heart] Me.” Her puzzle pieces allow her to see beauty and imagine new landscapes such as Paris. Lanesha draws strength, too, from being able to paint her bedroom blue. She’s learned that she can complete projects on her own.

Faith also supports Lanesha’s positive outlook. Her perception of the world isn’t static. There are things seen and unseen. Good and bad can ebb and flow. She is not afraid of ghosts, of death. In her world, the human spirit doesn’t die. Most significantly, she’s been taught, always, eventually, “the universe shines down with love.”

Lanesha was born with a caul—what’s the significance of her caul? Several characters in the book see ghosts and ghosts—both neutral and benevolent—are a real presence in the book. Can you talk about them. What is it they are looking for?

Lanesha, when she first spoke, told me she was “born with a caul.” A caul is a portion of the amniotic sac that sometimes forms a veil over a newborn’s face. In folklore, this means the child will have “sight.” By announcing her gift, Lanesha was heralding her southern heritage. She was telling me, matter-of-factly, that she accepted and experienced mysteries.

It’s impossible to live in New Orleans without experiencing remnants of the past. The architecture, the churches, the above ground cemeteries, and even the music, all incorporate ghosts and echoes of slavery and French and Spanish colonization. Particularly, for African Americans, New Orleans is where African-based spiritual beliefs blended with Catholicism. It is the birthplace of ragtime and jazz, rhythms inspired by African drums. It is a place where medicinal healing by slaves and native peoples produced a “roots” based, holistic tradition. In New Orleans, many African Americans do not believe the dead are accessible. It is not uncommon for someone to talk about receiving comfort and guidance from their ancestors. Dreams, spiritual visitations, and talking with the dead are all part of folklore and cultural and religious traditions.

The ghosts in the book help, I think, to deepen the “sense of place.” New Orleans is a uniquely American city—a mixed-blood stew, historically, and in the present.

Most of the ghosts

aren’t ready to move on. They feel comfortable, like Lanesha, living in two worlds, the seen and the unseen. In a sense, the ghosts are Lanesha’s alternative community.

In “coming of age,” tales, there is always a moment where the child ascends. Mama Ya-Ya is old with waning powers. Her inability to interpret Katrina’s signs is a call for the next generation, for Lanesha, to take charge. This is a natural cycle. The young with their energy and education replace elders who sustained the world as they knew it. Lanesha is getting ready to shape the world, as she knows it—and she “knows” the world as Mama Ya-Ya and her teachers have taught her. The ghosts keep silent about the impending storm because 1) they’ve seen it all, their sense of time is infinite; but their silence, coupled with Mama Ya-Ya’s silence, provides space for Lanesha to find her voice. And she does. To me, this is life. Parents, teachers, and ancestral ghosts (history, if you prefer) will ultimately give way to the next generation. Children will, one day, rule the world.

Mention of bridges appear throughout the book. Lanesha’s teacher tells the girl she would make a great bridge builder/engineer. Mama Ya-Ya says that Lanesha’s “feet bridge two worlds.” What can we hope for a bright future for Lanesha? (For New Orleans?)

Bridges kept many New Orleans citizens above water. Bridges took then to a safer place. Bridges occupy a nether world, a space that seems to defy air, land, and water. Bridges are signifiers for human ingenuity, intelligence, and interconnected-ness.

I have always thought New Orleans would thrive, no matter what. Hurricanes, land erosion, the BP oil spill have challenged my optimism. But there are thousands of Laneshas and TaShons in New Orleans who will not be daunted. As nature heals what humanity has done to it, I think lots of good people will be there, too—healing and loving a unique state back to health. It will take time. Louisianans have the requisite grit, determination, and abounding love.

This is your first for young readers. How did that happen? (& have you thought about writing others for this audience?)

I have ALWAYS wanted to write for children. My entire life I’ve been trying to become good enough, confident enough to write for children. Now that Ninth Ward is born, I feel reenergized. I’ve drafted a young adult novel and I’m starting on a new middle grade adventure.

Recent Comments