Award-winning author Jewell Parker Rhodes (Bayou Magic) kept booksellers at last week’s Children’s Institute 3 spellbound during her closing keynote, “Diversity and Character-Driven Stories,” about the next civil rights frontier: diversity. “[Diversity] isn’t about political correctness,” she said. “Nor is diversity a passing fashion; rather, it is a significant struggle to see if America can fulfill its civil rights promises of inclusivity —of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Below is the complete text of her speech, which drew a standing ovation from the crowd. The speech is reprinted with permission of the author.

I was born in a ghetto on the North Side of Pittsburgh. I was born as Emmett Till was dying and the civil rights era was being born.

I was lost, waiting to be found.

My mother abandoned me as an infant. Some say she left with another man; some say she was in prison for drugs. Family stories rose to the level of myth, with varying versions containing differing levels of truth and lies.

I grew up feeling “less than.” I was the sad, shy child hiding in the hall closet beneath coats. I’d wait for my grandmother’s voice to call—“Jewell, Jewell.” I was lost, waiting to be found. I thought being found, I’d be happier, better.

All the while I read stories. Stories with both truth and lies. Little Women, Black Beauty, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Nancy Drew.

I didn’t see me externally, but I felt me, my humanity.

I lived in a hyper-segregated community, and I didn’t see white people until I was five and was taken by bus [across the bridge] into downtown Pittsburgh. I had no experience with diversity. I’d only seen white people on book covers.

I inhaled books. I loved Classics Illustrated comic books. These were books that I could afford to buy after I turned in pop bottles for change. The Prince and the Pauper, Robinson Crusoe, A Journey to the Center of the Earth. Male narratives filled with adventure and self-discovery. I loved, too, the comic strip Prince Valiant, and when I was older, I read the Arthurian legends. Still I loved Prince Valiant the most—I wanted to be “valiant.”

While the books I read as a child lacked diversity in the strict sense, they didn’t lack values. Reading, I didn’t see me externally, but I felt me, my humanity.

Empathy during plot-driven conflict, struggle, and resolution can affirm and help break perceived barriers of race, class, gender, religion, and sexual orientation. Imaginative literature allayed my bitterness and anger and kept my imagination alive.

What is America if not an act of the imagination? Together, we shape, continue to shape, a narrative about a continually improving country trying to live up to its founding ideas.

However, I do believe not seeing myself in books, not reading books by people of color, that I almost missed my calling to be a writer. A frightening thought.

my family’s lies were just more stories.

I was a junior at Carnegie Mellon when I saw, on the library’s new fiction shelf, Gayl Jones’s Corregidora. Black women wrote books? It was a revelation. I switched my major the very next day. In my creative writing class, I was the only person of color. My classmates would say, “Why didn’t you tell me your characters were black?” “Why didn’t you tell me yours were white?” But truth be told, the experience confirmed that I, too, “read white” unless an author told me differently.

“Write what you know,” my instructor intoned. I wanted to write what I could imagine. I grabbed a Time-Life cookbook on Creole and Acadian cooking, and in the text it mentioned Bayou Teché, “Fais dodo” (a lullaby), and Marie Laveau. I stayed up all night writing a story that would become the seed for my novel Voodoo Dreams.

Only later, deep in my writing, did I realize that my grandmother was a natural-born storyteller, a master of the African American oral tradition, and it was this tradition that was calling and informing me. Only later did I realize that my family’s lies were just more stories. It took a decade before I became empowered to write from my culture and share it as any other writer would.

Grandmother migrated from the South, and besides being a Christian, she was a hoodoo woman. (Oh, the stories I could tell!) She’d come north to help my father raise his two small kids, and my aunt raise her three (her husband had been killed in a bar.) Grandmother took care of five kids under five. She died while parenting another generation of kids.

This is what I was told: Grandmother had been in the park with three little ones and had a heart attack or stroke—it’s not clear which. There were two hospitals, one on either side of Allegheny Commons and Riverview Park. There was Mercy, a cash-strapped Catholic hospital that had been one of the first to allow privileges for black doctors, and the more modern Allegheny General. Allegheny might have had in its first-floor ER the lifesaving equipment she needed; at Mercy, I was told, she died in an elevator. (I used to think Grandmother was so old; she was only 62.)

Grandmother died the spring I decided to become a writer. At Yaddo, writing chapter one of Voodoo Dreams, I felt her presence with me, directing me toward a deeper understanding of my heritage and the cultural and spiritual gifts she’d given me.

I remember Grandmother’s dream interpretations. Her stories about spirits and signs. Her sayings:

“Jewell, child, wear clean underwear. Always.”

“Do good and it’ll fly right back to you.”

“Everything of value can’t be seen.” (How true.)

“Jewell, child, there’s nobody better than you, and you’re no better than anyone else. We’re all a mixed-blood stew.”

We all bleed red.

And all good stories are, by their nature, diverse because they are about individualism, uniqueness.

Nonetheless, who gets published, what gets taught, is still dominated by an excluding narrative, a “master narrative” as Toni Morrison names it in Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (Vintage, 1993,) which privileges whiteness as the imaginative discourse. All of us—writers, publishers, teachers, librarians, booksellers—need to redouble, triple, our efforts so children can read and write and appreciate the diversity of their unique human selves. We must challenge the “master narrative” and replace it with true inclusivity.

Given 21st-century environmental and sustainability issues, global conflict and terrorism, lack of social mobility, and hate crimes reported and unreported, America can’t afford any child’s wasted mind, spirit, or voice. All stories have power, but that power is amplified when it mirrors specificities of race, class, religion, gender, health—physical and mental—and the myriad expressions of love and sexuality.

Without the mirror of me in Jones’s Corregidora, I wouldn’t have come into being. I wouldn’t have developed an empowered voice.

In 1845, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave: Written by Himself was published. The slave narrative as a literary form was, unfortunately, created in America. Douglass’s autobiography, his narrative, read like fiction—vivid, concrete, and scenic details driven by his not imagined but all-too-real character.

Autobiography: autos bios graphia. It means, literally, scribing oneself into being. Rebirthing oneself.

It’s not accidental that slaveholders disallowed literacy.

Having been forbidden to read and write, Douglass tapped into what had been only an oral form, and his writing intensified his arc of empowerment. The slave narrative form begins with “I was born.” Details of one’s early life are given. Then there’s a triumphant moment when the slave becomes spiritually free. With Douglass, it was during his battle with Covey, a slave breaker. Rebelling against mistreatment, Douglass fights Covey for nearly two hours. Covey backed down. Douglass wasn’t his property. Nonetheless, Douglass had changed the narrative of a black man submitting to a white man. He declared: “I did not hesitate to let it be known…that the white man who expected to succeed in whipping, must also succeed in killing me.” Later, becoming physically free, while significant, was anticlimactic to that interior recognition of selfhood. The only other moment to supersede Douglass’s spiritual moment of freedom was the act of writing his story, “by himself,” for all the world to read. I am Douglass. I am Jewell.

“I am.” Being able to say “I am” is the greatest civil right for all of us. Standing on our own two feet, comfortable and free to be “I am,” will lessen, I truly believe, any urge to oppress, to make someone else “other.” This is why we need diverse books. It isn’t about political correctness. Nor is diversity a passing fashion; rather, it is a significant struggle to see if America can fulfill its civil rights promises of inclusivity—of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. America’s story isn’t done. Freedom comes from empowered voices advocating for justice. Handing a book to a child, you—all of you—are influencing our country’s future story.

In children’s literature, I define diversity as the celebration of unique characters, a celebration of their heritage and culture, and their exterior and interior selves with the deepest sense of empathy and humanity.

Imaginative mirrors encourage all of us to be comfortable in our own skin. No one has to feel less than. Ever. All are included, none excluded, and everyone’s narrative is as important as any other’s. The more narrative threads we add—the rainbow threads, the diverse threads—the more American we become.

Douglass in his life’s story employed Aristotelian strategies—ethos, pathos, logos. Pivotal was his depiction of his mistress, who, formerly “kind and tender-hearted,” became under slavery’s influence cruel and stone-hearted. “Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me,” wrote Douglass.

Slavery is as injurious to the slaveholder as it is to the slave. Though an African made into an African American, sui generis, forcefully through slavery, Douglass demonstrated his learning, his empathy, his American-ness, by recognizing that the nation holds together, evolves together, through common good and understanding.

Lack of diversity is as injurious to me as it is to you. Injurious to everyone.

Diversity is not a monthly but an everyday event. Kids are smart—they know it’s fairer that everyone’s stories should be celebrated all the time.

Offering a book to a child is a life-enhancing act. Booksellers, continue to offer books based upon content. The story of coming into being, “coming of age,” is as powerful as ever. This story is as old as time, but individualization makes it continually new.

Though my heritage includes Choctaw, French Canadian, Irish American, and credible evidence, on my mother’s side, of direct descent from a master who impregnated his slave. I was raised with the “narrative” of one drop of black blood. Legally, this was a test for enslavement.

I am and always will self-identify as an African American woman. (Though I can’t wait to take my National Geographic DNA test.)

My husband (we’ve just celebrated 30 years of marriage) is a six-foot-four Norwegian Scots-Irish man.

It is indeed the content of our characters that determines love. Just like having almost missed my calling as a writer, by not seeing interracial couples mirrored, I almost missed my true love.

I almost missed my children, too. I agreed to marry, but I didn’t want to have children; I couldn’t envision a world or citizenry that would welcome them.

“People are people are people,” my husband said. “We shouldn’t patronize our children to be.” He was right.

We have a wonderful daughter and son. My daughter is light, like her father. My son is brown, like me. At times I was mistaken for my daughter’s nanny. There were times when people assumed my husband had adopted his son. Too many times to count when strangers would declare our children couldn’t possibly be brother and sister. (Their features are the same; it’s only skin tone that varies.) Times when I worried one day my son might be harassed because he was dating a white woman… rather than being with his sister.

When Rodney King was brutalized, our family drove up the coast of California searching for refuge. Both of us were terrified at the thought that our three-year-old, grown strong and tall, might one day be seen as a threat.

Still, my husband and I worked hard to allow our children the right to define themselves. My daughter identifies as a black woman. My son, who has heard the “being safe while black” talks, doesn’t choose any race.

The world has changed, and my children and their friends are breaking barriers, prejudices. It’s the evolving story of our country. Events I couldn’t believe I’d ever see have come to pass because of fellow citizens living new narratives of what makes family, a good society.

Today, I am more convinced than ever that as adults we sometimes get in our children’s way. We have too much conflicted history, too many worries and wounds. We forget that our power (and that of the community around us) is not to give up, not to quit—to unlock our children’s full potential as citizens.

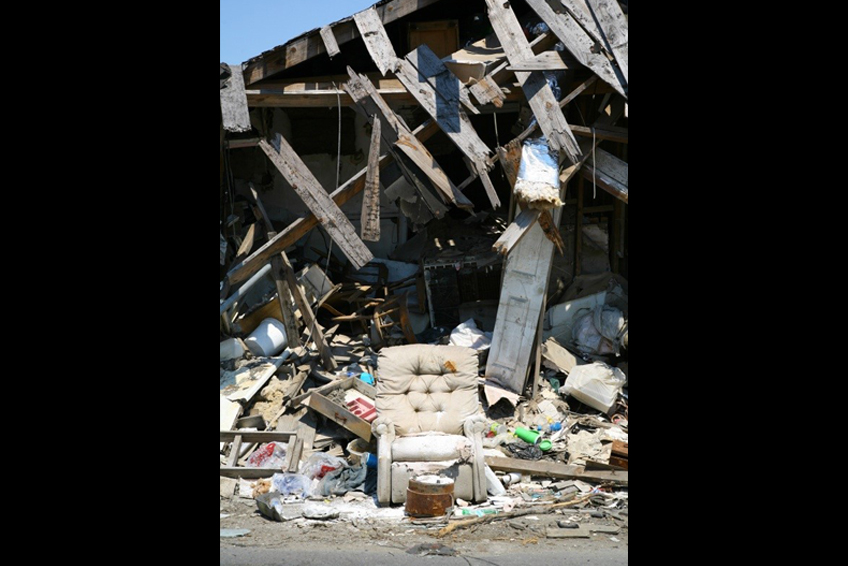

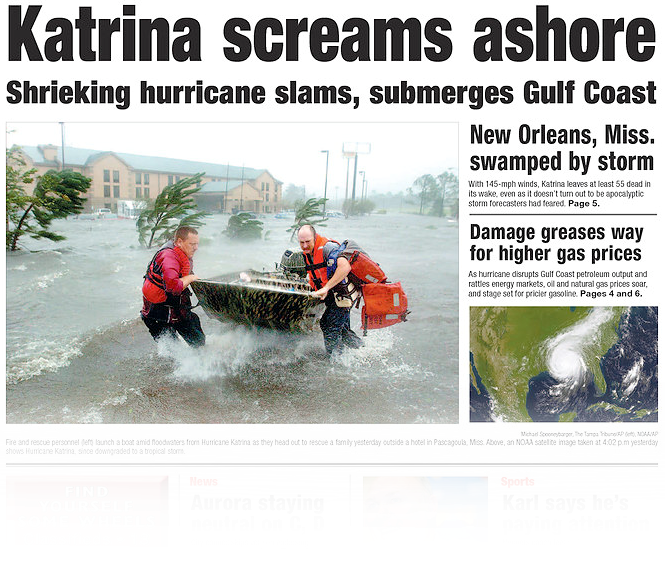

I’ve been to all-white schools, all-black schools, and mixed-race schools and have seen illustrations of beautiful black and brown faces of Lanesha’s Ninth Ward world taped to the walls. There’s recognition of race, but the discussion is always about how strong, how brave, how spiritually and math smart, how rich in love Lanesha is. Kids search for what’s relevant, what connects with their life… NOW. They know bad things happen, like Hurricane Katrina. Through character-driven stories, they explore what it’s like to survive, thrive, and become more themselves.

For me, I must admit it is extra sweet when a brown girl whispers, “Lanesha looks like me.” Or says, “Mama Ya Ya is like my grandmother.”

In Sugar, an ex-slave child wonders: If I’m free, why can’t I play with the former master’s son? Or be friends with the Chinese? Why does society still divide us?

Kids know it’s more exciting being friends with everyone. And though my jacket covers only show girls, my stories are always about a strong boy-and-girl friendship. (As I am mother to a son and daughter, how could they not be?)

In Bayou Magic, I wrote about African goddess-mermaids who accompanied slaves to America. Recently, in Minnesota schools, I talked with girls about how the African descendent mermaids were preferable to the Western Ariel, who changed her identity—inside and out—to marry a prince.

Booksellers, children’s booksellers—every day you are on the front lines, informing parents and teachers.

When a parent says about a book, “That’s not my child’s world,” remind her or him of the future. Social fluency will be the new currency of success. Not experiencing diversity challenges our kids’ future in the global workforce. It handicaps them from making America and the world more livable and just.

When a teacher says, “I don’t feel qualified teaching this experience,” remind them that they have a human heart and that the writer is their partner in connecting stories to kids.

Encourage your favorite writers to write more-diverse books. Humanity and empathy qualify us all. Perhaps as a ’60s legacy, some folks feel they can’t write about ethnic cultures. Hogwash. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” In other words, don’t stereotype. Do research and write with empathy.

Booksellers, your greatest power is that you select and arrange on your shelves which stories should be offered to children. How cool is that—how powerful is that! Continue to fill your shelves with diverse literature, know those stories, and help children make connections. Connections not just ruled by characters’ exteriors but by their interior selves, their journeys, and the novels’ themes.

Diversity in books is a civil rights frontier. As a nation, we’ve made progress. My life’s story bears witness to that. I am optimistic about the future. We all should be. We’re united by our humanity, united by stories.

I celebrate each and every one of you as booksellers, as parents, grandparents, as uncles, aunts, as individuals. Thank you for fulfilling the sacred trust of handing a book to a child.

April 30, 2015

Publishers Weekly

Recent Comments